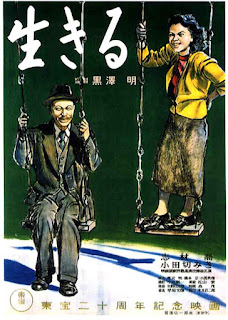

Film: Ikiru

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Country: Japan

Released: October 1952

Runtime: 143 minutes

Genre: Drama

Studio: Toho

Influenced: Shohei Imamura, Terrence Malick, Peter Weir, Hirokazu Koreeda, Alexander Payne, Oliver Hermanus

1952 saw the release of two of the best films ever made about ageing – Vittorio de Sica's Umberto D and Kurosawa's Ikiru, both in the same vein as Leo McCarey's classic Make Way For Tomorrow, about the tensions between generations during times of hardship. Umberto D is a little dated and overrated to my mind, but Ikiru is a masterpiece. Inspired by Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilych, Ikiru combines universal themes (approach of death, finding meaning in our lives, etc) and domestic Japanese ones (bureaucracy, sickness in children and adults, social struggles in the post-war Japanese state, etc).

Takashi Shimura plays the lead role of a widowed civil servant, Kanji Watanabe, who learns that he’s dying of stomach cancer. Stomach cancer rates were higher in Japan than anywhere else in the world at that time, and Kurosawa was tapping into public fears about disease and the fallout from the atomic bombings of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Scriptwriters Oguni and Hashimoto made an important contribution to the film, especially the distanced and emotionless narrator, freeing the film from the emotional pathos that might characterise a narrative about a dying man (we see an X-ray of his stomach cancer in the first shot of the movie). Watanabe’s disease is more than physical though; his sickness is also mental, borne out of bad values and poor choices.

His devotion to his work has come at the expense of his family and his personal happiness. “Don’t be late. Don’t take time off. Do no work ” – these were the three primary rules of Japanese bureaucracy at the time. The film's opening montage is a wonderful visual demonstration of how the mothers wanting a new playground get the official runaround. Meanwhile, Watanabe is a mysterious figure, we don’t know why he’s suddenly not in the office and taking a very rare day off to visit the hospital. While there, we see his pained expressions in closeup and, in line with Japanese medical practice at the time (to preserve public morale), he’s lied to about his stomach cancer – instead he’s told it’s a mild ulcer. But he knows.

Watanabe’s son and wife represent the new generation, more commercially-minded and inquisitive. Unlike western portrayals of a dying person on film, there is no melodrama and the way Watanabe doesn’t tell his son about his disease is typically Japanese. We then have a series of flashback vignettes showing his wife’s funeral, his brother’s advice about not prioritising his work, his son playing baseball, his son in hospital and his son off to war – all showing estrangement between father and son.

In the film’s second act, Watanabe has disappeared for 5 days and appears to be contemplating suicide. He meets with a bohemian writer in a bar who helps him to go out and live a better life, starting with a pachinko parlour, then a beer hall and brothel, all of which show an emerging underground culture in big cities like Tokyo after the war. Watanabe singing “life is brief” is one of the film’s most emotional moments and Shimura’s acting is so open and convincing. Some of the shots here are mesmerising, like the reflections of the city at night on the car window as we see Watanabe travelling inside. Yet this new debauched and individualistic world will not be a fruitful path for Watanabe to follow.

Was Kurosawa also influenced by Dante when making this film? The bohemian novelist character is like Virgil taking the pilgrim Watanabe first through hell before finally helping him attain a state of heavenly enlightenment. Watanabe is also drawn to the youthful glow of Toyo (Miki Odagiri) in a similar way to Dante's pilgrim being pulled along by the allure of Beatrice. Toyo's childlike enthusiasm and irreverence helps him rediscover his sense of joy and the scene in the tea house where she tells him all her office nicknames is so lovely. Kurosawa was influenced by Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Shakespeare, so it's not a stretch to think there would be echoes of Dante in his work too.

Kurosawa is atypical as a Japanese director in that he doesn’t always stress the traditional values of family, work and country. The film not only shows the breakdown of the nuclear family but also class and social divisions, i.e. Toyo’s tough life compared to other girls of her generation. Ikiru is such a personal film too – the anecdote Watanabe uses to describe to Toyo his horror at finding out he has cancer (nearly drowning as a kid) is actually drawn from Kurosawa’s own life. Watanabe then gets the flash of insight that allows him to find meaning in his life (I won’t say what to avoid spoilers). In the coda to the second act, we see Watanabe acting with a renewed vigour and moral authority, showing how willpower and determination can overcome any situation that humans are faced with.

The structure of the film’s third and final act is complex, involving 13 flashbacks in under 20 minutes, but the payoff for the audience is immensely rewarding and emotional. Like Rashomon, it shows Kurosawa’s appetite for experimenting with unconventional storytelling techniques (the idea for Watanabe to die midway through the film was actually the idea of screenwriter Oguni). One of the film's recurring motifs is Watanabe's hat. When the policeman recounts how happy Watanabe was on the swing in his last moments, Mitsuo looks down at his father’s hat in remembrance. That moment never fails to touch me deeply. The final epiphany scene is, for me, one of the greatest moments in all of cinema. But in the coda, Kurosawa shows bureaucracy prevailing and the cycle starting again. Addressing his own personal anxiety at the time, Kurosawa seems to be saying that we are only alive when doing meaningful work.

Comments