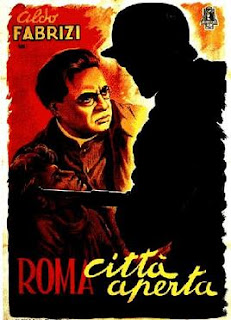

Film: Roma, Città Aperta

Director: Roberto Rossellini

Country: Italy

Released: September 1945

Runtime: 105 minutes

Genre: Neorealism

Studio: Minerva

Influenced: Ingrid Bergman, Vittorio de Sica, Scorsese, Robert Altman

To explain the title, when Mussolini fell from power in the summer of 1943, Rome was declared an "open city", in effect abandoned by the Italian army to allow western allies and local partisans to capture it without causing too much destruction to the city. However, the Nazis still had control of Rome and it took almost a year of fighting, including the bombing of buildings, to end their occupation. What was left in the ruins was an Italian population living in fear and poverty, and this historical backdrop is the film's setting. Roma, Città Aperta helped to humanise an Italian people who were just emerging from years of Fascist rule under Mussolini, while also putting a new cinematic movement (later dubbed "neorealism") on the map with a global audience.

Roberto Rossellini was called the "father of modern cinema" by the Cahiers du Cinéma for the way this film revolutionised the language of cinema in the post-WWII era. But like the war itself, this film required a strong alliance to get over the line – Sergio Amidei was a communist intellectual engaged in the resistance, while Alberto Consiglio was a journalist and Catholic monarchist seeking to write the story of a priest killed by the Nazis, and together the two screenwriters and friends shared their ideas with director Rossellini. The project developed from a short, episodic film to a full feature-length movie that intertwined the various narrative elements, putting Italian fascism in the background and placing the focus on Communist and Catholic partisans and the ordinary people of Rome suffering under Nazi occupation.

Aldo Fabrizi as Don Pietro and Anna Magnani as Pina are the film’s stars, both comic actors cast cleverly by Rossellini in tragic roles. Scriptwriters Amidei, Consiglio and a young Federico Fellini (who was brought in by Rossellini) took the brave decision to kill Pina off halfway through the film, on her wedding night, to produce the maximum emotional shock for audiences, just one of the ways that the film marks a revolution in cinema. The film's ending is also a clear departure from Hollywood, unflinching in its portrayal of the deaths of the resistance agent Manfredi (played by Marcello Pagliero) by torture and the priest Don Pietro by firing squad. The expressionist lighting used by Rossellini to portray Manfredi in his dying moments gives him the air of a Christ-like figure.

Throughout the film, there's a strong and heroic link made between Christianity and Marxism, while the Nazis and Italian traitors are shown as the "maledetti" (the damned), as Don Pietro calls them. Rossellini shows his contempt for the Italian women who befriended Nazi officers and betrayed the secrets of the communist cause, while many of the Nazi characters like Bergmann and Ingrid have gay mannerisms, as if to link homosexuality with depravity. This and the way the film glosses over the contribution of Italian fascism are two of the film's blind spots. At the end of the movie, we see a new generation of young boys, effectively Italy's future, walking away from the horrors of the past and into the city of liberated Rome. Such was its cultural impact, the film played for 20 consecutive months in New York, helping build an audience for foreign film in the United States and attracting the attention of Ingrid Bergman.

Roma, Città Aperta was the first of three Rossellini films known as his war trilogy, along with Paisà (1946) and Germania Anno Zero (1948), and is by far the most compelling of the three. For me, there's a falling-off throughout the trilogy, but Paisà is worth watching if you can bear the very amateur acting (starting with Joe from Jersey), and the rapid-fire and unsatisfying nature of many of the short stories or film vignettes. The elements of neorealism (non-professional actors, naturalist settings, etc) are stronger in Paisà but it's also more uneven in terms of image quality, audio and style (going from documentary to neorealism to melodrama, and everywhere in between).

Some of the narrative elements are engaging – the story of Fred and Francesca is quietly heartbreaking, while the story of Lupo and the English girl is high on melodrama. Episode four is pleasant to start with, a meeting between the Franciscan monks and the American military chaplains (Catholic, Protestant and Jew). They offer the impoverished monks various riches, from cigarettes to Hersheys chocolate and tinned milk, but the dialogue is wooden, the editing poor in parts and it's a strange choice to show Catholic religious intolerance of Jews in the immediate aftermath of WWII.

Finally, Germania Anno Zero is a harrowing film, and also slightly odd and creepy at times (notably the paedophile ex-teacher) and I've no idea why it's rated so highly, other than the fact that it's linked with an avant-garde director like Rossellini. He would also go on to make another trilogy of films, this time with his actress wife Ingrid Bergman – Stromboli (1950), Europe '51 (1952) and Journey to Italy (1954) – all influential on the French nouvelle vague and auteurs like Ingmar Bergman. Journey to Italy in particular is highly-rated among critics, but I have to admit I found the dialogue wooden, the editing clumsy and the plot banal. Perhaps that's the point – the landscape, particularly the ruins of Pompeii, are supposed to symbolise the breakdown of a marriage – but the film lacks the energy and craft of Roma, Città Aperta.

Comments